Nathan Deatrick

My Plea for the Plowboy

October 6, 2024

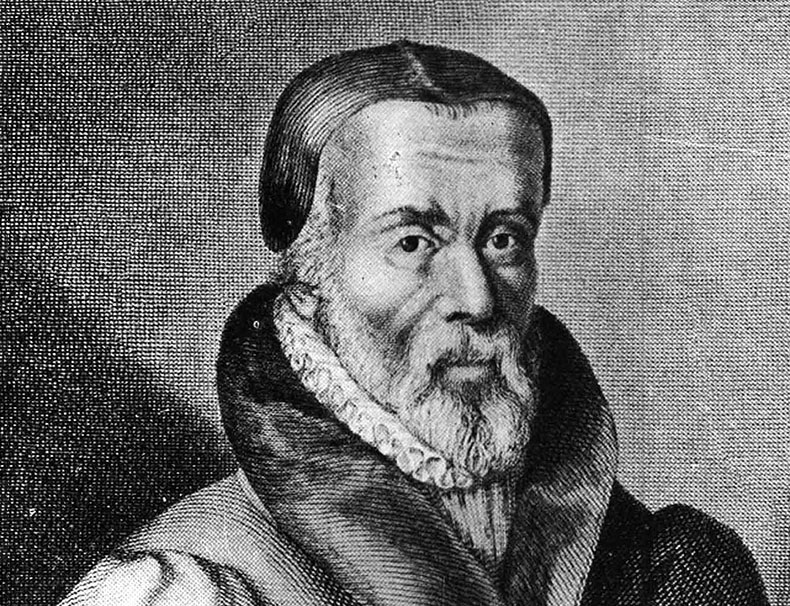

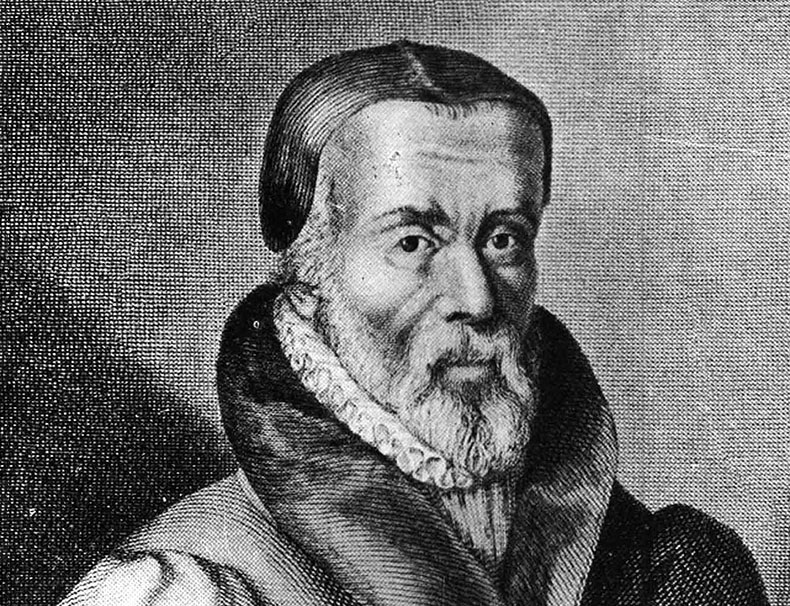

William Tyndale is arguably the most important figure in the history of the English Bible. According to David Daniell, the renowned historian, over 80% of our NT derives from Tyndale’s translation work.1David Daniell, The Bible in English: Its History and Influence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 136. And of the OT books he translated, he has been followed an estimated 76% of the time by subsequent translations.2Brian Moynahan, God’s Bestseller: William Tyndale, Thomas More, and the Writing of the English Bible—A Story of Martyrdom and Betrayal (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003), 1.

All of this came from a man who lived most of his adult life on the run, exiled from his native country—and who was ultimately betrayed and burned at the stake as a martyr for his consuming desire to make the Bible accessible in the English language of his day. For me, however, one of the most poignant scenes of Tyndale’s life took place when he challenged the blasphemous statement of a learned Roman Catholic, who had just boasted, “We were better without God’s laws than the Pope’s.”3R. Demaus, William Tyndale: A Biography (London: The Gresham Press, 1871), 63.

Tyndale’s passionate reply echoes in my soul 500 years later:

If God spare my life ere many years, I will cause a boy that driveth the plough, shall know more of the scriptures than thou dost.4David Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 79.

His heart yearned to translate the Bible into such a simple vernacular that the plowboy of England could read and understand the very words of the living God. My plea is that Tyndale’s passion would ignite my generation to such a degree that the plowboy of today can have God’s Word in the English of his day.

William Tyndale, father of the English Bible

My plea for consistency

My plea, first of all, is for consistency. For my entire Christian life I have hailed from fundamental Baptist Christianity. I have used only the King James Version in all my preaching and teaching, and I continue to have profound love and appreciation for the KJV. It has a prominent place not merely in Bible history but in my personal history. This being said, over the last 18 months I have come to the hard-fought and honest conclusion that the thoughtful acceptance and use of faithful modern versions is not at all inconsistent with our principles, nor our past as fundamental Baptists.

In reality, our principles actually argue the case for the acceptance of good current translations, including those translations which hold firmly to a TR-based tradition. We rightfully disdain the mindset of the Dark Ages that restricted access to the Bible from the common man, not only by keeping it chained up in churches, but also metaphorically by keeping it chained up in language that he couldn’t understand! The entrance of God’s Word gives light; it gives understanding to the simple. Common people heard Jesus gladly. Paul in 1 Corinthians 14:9–11 argued for words “easy to be understood” so that meaning and ultimately life-changing edification could be experienced. Interestingly, the KJV translators used this very passage in their preface to the 1611 as a justification for their translation work. Their arguments in that preface also justify the ongoing need for future translations and updates beyond their own work. One of the marvels of the day of Pentecost is that every man heard the wonderful works of God in his own language. We must realize that because of natural changes which occur over time in a language— words “die” and words change meaning within a language—that Jacobean and Elizabethan English are not the English of the 21st century. So even the gracious action of God recorded in Acts 2 is a precedent for our understanding the need of and accepting updates to our Bibles through current translations, so that men can hear and understand, in their own language, the wonderful works of God.

For years I have heard, from within our own circles, the openness for updates to the KJV, but with the passing of time I’ve come to see that this openness is more theoretical than actual. Many viable options that have been offered since the mid-’70s, when I was born, get shot down with various attacks or excuses. I’m increasingly convinced that these excuses are not as much based on principle but more on the politics of our fundamental Baptist circles. Sadly, we have let extremists define the terms of the debate over English Bible translation, and in so doing we are constantly painting ourselves into smaller and smaller extra-biblical corners. We’re defending traditions about the Bible that God neither revealed nor commanded in His Word, and all the while adamantly seeking to avoid association with Ruckmanism. Ironically though, the leaven of Peter Ruckman’s aberrant teachings has infiltrated our doctrine of bibliology more often than is admitted or recognized. For years, my Dad, a Baptist pastor of more than 50 years, has colloquially observed that these discussions often devolve into men trying to be “righter than right.” Truth be told, becoming more right than right can lead to error; just ask the Pharisees!

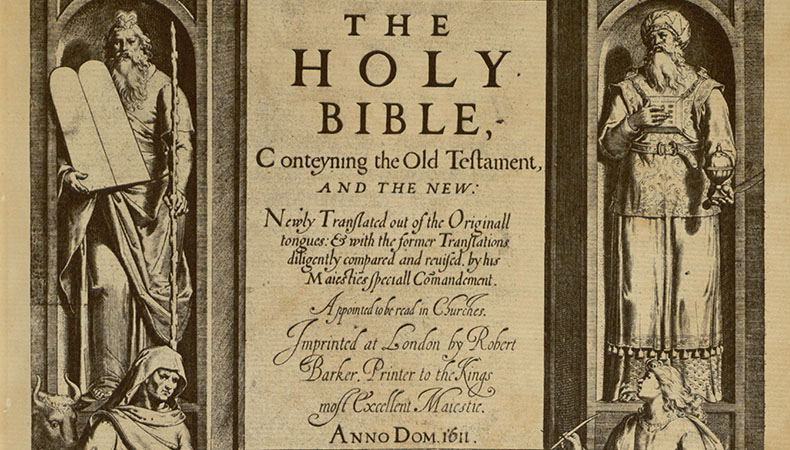

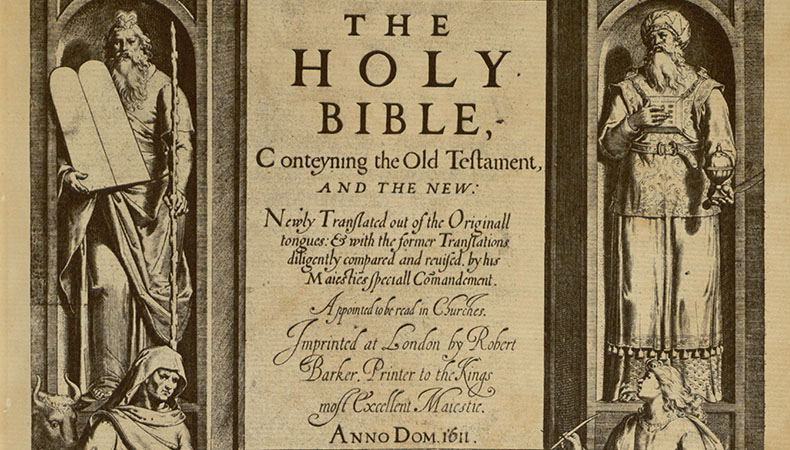

Furthermore, consistency demands that we recognize another aspect of this issue. So many of the accusations that are leveled against good, viable, modern, even TR-based updates to the KJV, could just as well have been used against the KJV when it was first released. One of the go-to criticisms against modern versions is the presence of alternate translations in the margin or footnotes, and, yet, so it was with the original KJV 1611. The publication of modern versions is often criticized for being economically motivated, and yet a study of the history of the KJV exposes the fact that making money was unquestionably a significant part of what drove its publication.5“Since the time of Henry VIII, Bibles printed within England by official sanction—such as Matthew’s Bible, The Great Bible, and the Bishop’s Bible—were subject to a trade monopoly. The monarch granted a ‘privilege’ to favored subjects allowing them a monopoly on the production of certain types of Bible—an honor or favor usually indicated with the word cum privilegio on the title page of the Bible in question. The crown, in turn received a proportion of the ‘royalty’ paid to the holder of the privilege. … It will thus be clear that the use of the King’s printer for this important new translation did not rest upon any perception that this would ensure a more accurate or reliable printing, but upon the belief that this was potentially a profitable project that would bring financial advantage to Barker and his partners.” Alister McGrath, In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation, a Language, and a Culture (New York: Anchor Books, 2001), 198–199.

All of the translators were paedobaptists. All things considered, while we’re grateful for the remarkable place the KJV holds in the history of the English Bible, we should collectively shudder when we hear of a fundamental Baptist pastor from a major conference platform contending that in the same way the Spirit of God came on the virgin Mary at the conception of Jesus in her womb, so He hovered over Hampton Court as the translators did their work from 1604–1611. I know of no other way to describe this but as heresy, regardless of how many “amens” it garnered. And the KJV translators definitely would not have said an amen to this claim! In their preface they specifically refute the claim that they were inspired like the apostles.7“[There is] no cause therefore why the word translated should be denied to be the word, or forbidden to be current [that is, circulated], notwithstanding that some imperfections and blemishes may be noted in the setting forth of it. For [we ask:] whatever was perfect under the sun, where Apostles or apostolic men, that is, men endued with an extraordinary measure of God’s Spirit, and privileged with the privilege of infallibility, had not their hand?”

My point in bringing these issues up is not to attack the KJV, but rather to further my plea for honesty and consistency. Can I simply say it this way? The KJV was a modern version in the first half of the 17th century. When the KJV entered the Bible market of its day, the very same reasons that have been used to dismiss its modern counterparts since the 1970s were true of the KJV as well. The KJV was not immediately accepted, and it actually took decades to become the primary Bible of the English-speaking world. In fact, when Miles Smith penned the preface to the KJV, he quoted from the Geneva Bible. After the publication of the KJV, a number of the translators not only continued to use the Geneva Bible in their writing and preaching, but several were also actually a part of later efforts to update the KJV for subsequent printings and editions.8Gordon Campbell, Bible: The Story of the King James Version (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 116–117.

So, consistency with our principles necessitates that we be willing to accept updates to the KJV—such as are already available—and that we admit that the very arguments that are often used to “disqualify” these modern, TR-based updates (such as the NKJV, MEV, KJV21, KJVER and SKJV) could have been leveled against the KJV itself.

The frontispiece to the 1611 KJV.

If Spurgeon was calling for updates in his day, then what does that mean for us today? We must acknowledge, as our fundamentalist predecessors did, that the KJV is subject to the limits of translation, as well as to those normal changes that occur in a language over time, and therefore, of necessity, would need to be updated. This was the prevailing view of fundamentalism up through the 1970s, before the errors of the novel KJVOnlyism of David Otis Fuller, Peter Ruckman, Jack Hyles, and their protégés rose up from our midst. Therefore, it is consistent with our past as fundamental Baptists to recognize the need not only for updates to the KJV, but also to allow room for them.

My plea for the Great Commission

My plea for the plowboy is based, secondly, on the commission, The Great Commission. It is in the spirit of Tyndale that I am compelled to make a plea for the plowboys of our own day to any of my brethren who will read this. The plowboys of our world need a Bible they can understand just as much as the plowboys of Tyndale’s world did. It is estimated that the literacy rates in the 16th and 17th centuries were 16% and 30% respectively. While the overall rates of literacy in our world today may be higher, it is still staggering to consider that an estimated 54% of adults in the US read at a 6th grade reading level or below. Twenty-one percent of adults 18 and above in the US are considered functionally illiterate—a full fifth! And, what we can’t miss is that these statistics are based on reading modern English, not Elizabethan English—and there is a profound difference between them. The plowboys are still in desperate need of God’s Word in their language, and the answer is not to teach them Elizabethan English.

More and more, we’re hearing of the struggles of young missionaries and church planters laboring to use the KJV in countries that may speak an elementary level of modern English, but in a bilingual or even trilingual context. These countries, however, would barely qualify as an ESL setting, if even an ETL or EFL level.10English as a third or fourth language. Yet because Wikipedia tells us that places like the Solomon Islands or Liberia or The Gambia speak English, some American fundamental Baptists insist that the missionary use the KJV. The plowboys of numerous mission fields struggle enough as it is with modern English without being pressed to use a Bible written in Elizabethan English—an English, by the way, with which a growing number of Americans struggle. In truth, pastors, and churches in the multi-ethnic inner-cities of the US are facing the same dilemma as their brethren on foreign fields. Admittedly, there are implications of this reality which are a tough pill for some to swallow, but a solution is at hand. The plowboys of our inner-cities need access to a Bible they, too, can understand.

We need to acknowledge that there’s a sense in which those of us who’ve only known and used the KJV are not the best judges of how desperate the plowboy’s situation really is. For me, processing the Elizabethan English of the KJV is pretty much second nature after over four decades of near daily interaction with it. But fewer and fewer people in the English speaking world have this as their background. Recently, for the sake of comparison and study, I have been doing daily reading in some modern English versions, in conjunction with my reading in the KJV. When I was sharing this with a good friend from a similar background to mine, he asked me if the modern versions were really all that much easier to understand. As I analyzed his question, it hit me that I’m not a fair judge to do such a comparison. When I read the KJV, my mind has a pre-programmed, “update-a-word” mechanism that automatically tells me that “prevent” actually means “to go before,” and that “let” means “to restrain,” and “conversation” means “citizenship” in Philippians 3:20 and “manner of life” in 1 Timothy 4:12, and “untoward” means “perverse,” and “leasing” means “lying,” and “iniquity” means “lawlessness,” and “besom” means “broom,” and on and on I could go. There are hundreds of KJV archaisms, verb forms, syntactical constructions, and words with fundamentally changed meanings that are second nature for me to process. Because of that, I am not a fair judge to do a truly objective comparison between the readability level of the KJV and other modern English versions. The plowboy is the real test. Can the plowboy understand KJV English? That is the question. And so it is for the plowboy that I make my plea. He needs a Bible, both reliable and readable, that he can understand. Reliability and readability are not mutually exclusive, rather they are interconnected. One does not have to be sacrificed for the sake of the other. God’s Word gives us the expectation for both. In fact, accuracy in translation is a two-sided coin. To focus on accuracy from the original language without due consideration of the accuracy of understanding—or readability—in the receptor language is to miss half of the work of good translation. Not only was this William Tyndale’s heartbeat, but I can also say that it is God’s heartbeat! In fact, it is God’s will!

Admittedly, a missionary on the field or a church planter in the inner city can use the KJV to preach, teach, and disciple in the public setting by implementing his pre-programmed, update-a-word mechanism, and he can do a decent job at it (though it will cost him valuable preaching time defining archaisms for his hearers). However, most of the people to whom he’s preaching likely do not have one of those mechanisms in their brains. What are they to do when they go home and try to read the Bible themselves? Do they become dependent on their pastor to explain what the Bible means? It pains me to say it, but it sounds very Catholic, not Baptist, when the pastor becomes indispensable to a person’s knowledge of what the Bible says. Part of what set me on these last 18 months of study and growth is the struggle of my younger brother, Michael, a missionary church planter in the Solomon Islands. I’ll never forget those long, uncomfortable phone calls that first came early in 2023, when he informed me that he was going to begin using the NKJV. At first, I doggedly resisted and tried to talk him out of it, mostly out of my fear of the political fallout. However, as he began to share the reality of his situation with me, as well as the reading he’d been doing, I became slowly, but clearly convinced to make the plea you now have in front of you. Part of his burden was not just the need for a modern English version to be preached in the public setting of the ministry there, but more than anything, his greater burden was for the discipleship and growth of the individual believers and families in their homes. I can still hear his heart, “Nathan, my people need a Bible they can understand at home as they daily seek to know God and lead their families, and they are not getting that from the KJV with its archaic English.” Based on principles like those I related earlier, and for the sake of the people God has called him to evangelize and disciple in the Solomon Islands, he made the decision to use the NKJV. Less than a week after he formally asked his mission board for permission to use a TR-based modern English translation so that his people could understand God’s Word both in public ministry and personal reading, he was removed from that board. He paid a dear price for his convictions, losing approximately half of his support and some friendships, too. But God has vindicated him. Everything he lost has been regained and much more. The work there has grown not only numerically but also, more importantly, in a spiritual way—because the plowboys of the Solomon Islands have a Bible they can better understand. And may I say that Michael is not alone in his dilemma and decision. His situation is increasingly common. So, my plea is based on the Great Commission. And, without any needless offense, I want to goad our consciences with this thought: A tradition such as KJVOnlyism seriously needs to be re-evaluated, if not relinquished, when it becomes an impediment to the Gospel of Christ and the growth of believers, whatever their geographical location.

My plea for commitment

Thirdly, from my heart for the plowboy, I want to plead for a commitment in two particular areas: a commitment to read and a commitment to reason.

A commitment to read

Over the last 18 months, I have purchased 30+ books on this issue, in addition to those I already owned. Some of those books have been agreeable to the position I was taught, but others have not. While some have not been agreeable, they still have an unquestioned fidelity to the Scriptures, a genuine Christlike kindness to their spirit, and a lucidity to their reasoning. All of them have been written by authors who have a high regard for the KJV, even if they advocate for the use of contemporary English translations. They all, with the exception of a couple of historians, would profess to be born-again believers who, as best I can determine, fit firmly in the evangelical or fundamentalist circles and who have a deep love for God’s Word. Reading more widely on this subject has edified me, opened my eyes, exposed me to significant blindspots that had limited my own thinking, convicted me that certain of my own views needed to be amended—and, all along the way, deepened my love for the Scriptures to a greater level than ever before. None of this reading has undermined my confidence in the Word of God; it has only strengthened it! This being said—and I hate to admit this—but in our circles, we are often guilty of doing our reading in an echo chamber on the KJV issue. I plead with you to read scholarly, balanced histories of the KJV like those I’ve referenced in the footnotes. Read the Translators to the Reader preface of the KJV along with detailed explanations of its intent; this is key to understanding how the translators themselves viewed their work. Read what authors on the “other side” of the version debate write regarding both their position and their critiques of KJVOnlyism. Read books on the history of the English language. Read books on translation philosophy and the agonizing, imperfect, and developing work that it always is. Above all, read the Bible for understanding, consciously depending on the Spirit of God as the Divine Teacher, to give you the clearest knowledge of Christ possible. I have had to discipline myself to make sure that even as I’ve done a gargantuan amount of reading about the Bible, that I stay in the Bible. And, in the interests of full transparency, I will admit that as I’ve read from some of these modern versions, I’ve had numerous “light-bulb” moments, as passages that I’d struggled understanding to this point in the KJV, came to clarity through the wording of a modern English version. In those moments, I was a plowboy. All of this reading has stirred this growing plea within me for the plowboys of my generation, and the next, and the next!

A commitment to reason

I’m also pleading for a commitment to reason, that is, to right thinking about the KJV issue. I’ve been embarrassed in some instances and convicted in others, as it relates to how KJVO advocates will attempt to support their position with faulty reasoning and logical fallacies. For instance, there are many wonderful passages in the Bible which speak to the supernatural nature and characteristics of Scripture in every generation, but to appeal to those passages as authority for making an exclusive claim of translational absolutism for the KJVO position is untenable. Whatever your view on the antecedent of the pronoun “them” in Psalm 12:6–7, David was not referring to the KJV alone when he penned these verses 3,000 years ago. Nor was he referring to the KJV alone when he wrote Psalm 138:2, as I heard a preacher contend at a large national conference just last year. This is the same preacher who also propagated the heretical concept that just as the Spirit of God came upon the virgin Mary to conceive Jesus in her womb, so the Spirit of God came upon the translators of the KJV as they did their work from 1604–1611. To say it bluntly, the KJV translators would have rejected such an outrageous comparison. The “incorruptible seed” of 1 Peter 1:23, is not referring to the KJV, as Jack Hyles taught in the 80s. Praise the Lord that folks are being born again by means of modern Bible versions. Modern versions are not the “corruptible seed,” nor are they an enemy of soul-winning. These passages and others are regularly used by KJVO advocates to support translational absolutism, and that is wrong thinking. One has to ask what did these passages mean before the Hampton Court Conference? To which texts, copies, or translations did they refer before 1611? What do they mean for believers in the rest of the world where there has never been a KJV? Without oversimplifying the answer to this question, these passages refer to the Word of God settled forever in Heaven, given to mankind in the originals, and passed on by faithful copies and translations to every generation in every location and language!

Furthermore, it is illogical to hold the KJVO position when the translators themselves were not KJVO by any definition. And too often KJVO advocates resort to ad hominem attacks on men who do not agree with them. This is frequently what happens when a person recognizes that he’s lost the logical high ground of truth or does not fully grasp the issues at hand. Worst of all, it is not Christlike! Dr. Charles Surrett, my former professor and colleague, regularly reminded us, “Our disposition is as important as our position.” How you say what you say is as important as what you say (Colossians 4:6). A viable position can be discredited by a bad disposition! It is also inconsistent and faulty reasoning to make the KJV the standard by which other translations are judged. Fidelity to the originals, not likeness to another translation, is the standard by which a good translation is to be judged. KJVO advocates will look at a particular passage in the KJV and then accuse another version of undermining cardinal doctrines of Scripture because a word is “omitted” in the parallel passage of that version, and yet, in so doing they fail to acknowledge two vital factors: 1) That the doctrine in question is still clearly taught in numerous other passages in that version, but, even more importantly to realize, 2) If comparison between versions is the standard, there are passages where a modern version includes a “key” word, and it is actually “omitted” in the KJV.11Matt 16:21; Matt 27:50; Mark 16:19; Acts 10:48; Acts 24:24; Rom 8:11; Rom 9:5; 1 Cor 6:11; 2 Thess 2:8; 2 Peter 1:1; Rev 1:8; Rev 4:11.

Does this mean that the KJV is guilty of undermining key doctrines of Scripture? Could this not be a case of the “pot calling the kettle black,” or the need to realize that this road runs both ways? It must be kept in mind that the KJV itself is the fruit of translation work, not the foundation by which other translations are to be judged!

Another caveat: we should be wary of the simplistic distinction that is often made regarding formal and dynamic equivalence translations. There are actually more than two legitimate forms of translation. And often, multiple forms are necessary in a single work in order to translate accurately and accessibly! However, KJVO proponents often speak of the absolute superiority of the KJV based on its exclusivity as a formal equivalent translation—but then fail to note that there are occurrences of dynamic and functional equivalence even in the KJV.12Kenneth L. Bradstreet, The King James Version in History (Enumclaw, WA: Pleasant Word, 2004), 120–122. For example: the KJV translators used “God forbid” in numerous passages and “God save the King” in 1 Sam 10:24; 2 Sam 16:16; 2 Kgs 11:12; and 2 Chr 23:11. Both are accurate translations; neither is a literal one.

So, I plead with my brethren, be committed to reading and reason—right thinking! Avoid non sequiturs, logical fallacies, and inconsistencies.

My plea for compassion

Finally, in my plea for the plowboy, I ask for there to be compassion! Assuming that most who read this are Baptist, or at least Baptistic, I plead for compassion based on our distinctives. I’ve periodically noted, on issues like this, that some brethren actually become “half-Baptists.” They seemingly ignore distinctives like the autonomy of the local church, the priesthood of the believer, individual soul liberty, and even the Bible as our sole rule of faith and practice. That’s four out of eight missed, thus producing a “half-Baptist.” I reference my friend Dr. Charles Surrett again. He has graciously maintained a steady TR/KJV position for years, and has written extensively on his reasons for doing so. Men who do not agree with him have testified to the responsible and careful manner in which he has articulated and held his position. In his book, Which Greek Text? The Debate Among Fundamentalists, he made this simple, but profound statement, “In summary, since God did not promise to inspire future translations, there is no Biblical basis to believe in their inspiration, and the issue of translations should not become a test of fellowship.”13Charles L. Surrett, Which Greek Text? The Debate Among Fundamentalists (Kings Mountain, NC: Surrett Family Publications, 1999), 104. May it ever be so!

Compassion can also be expressed as we strive to maintain balance. Balance is not a static position; it requires constant adjustment. And adjustment is definitely needed on this issue for the sake of the plowboy, as well as those of the coming generations who will minister to them. We do the next generation no favors if we double down on this issue, painting ourselves (and unfortunately them) into an even tighter corner. All the while, the natural changes occurring in the English language with the passage of time make KJVOnlyism all the more untenable and the Elizabethan English of the KJV progressively more unintelligible. May we strive for balance—moderation, reasonableness (Philippians 4:5)—on this issue.

It follows also then that there should be a benevolence that marks us, as we seek to demonstrate Biblical compassion: benevolence both for the needs of the plowboy and for the next generation of pastors, church-planters, and missionaries who will win and disciple them. This benevolence can be demonstrated by giving them legitimate room to implement the choices they need to make in order to use the best Bible possible to reach the plowboy of their generation in their corner of the harvest field. This spirit of Christlike benevolence will also keep us from automatically accusing a young man of compromise who, for the sake of the plowboys where he labors, is compelled to use an updated version. This slippery slope argument is yet another fallacy of logic that is often motivated by fear, not faith or fact!

Last year I was deeply challenged and encouraged as well by my conversation with an older pastor friend, who is a faithful fundamental Baptist. He anticipates ten more good years of pastoring before retirement and is contemplating leading his church to make the change to a good updated version of the Bible in his final years. Part of his reasoning is that he’s the one who has the pastoral capital to do it. This will save his potential successor—almost certainly a younger man—from having to lead in this step forward. This is a benevolence that stems from a compassion for the next generation, reminding me of Will Allen Dromgoole’s classic poem, The Bridge Builder. Granted, this pastor is sensitive to the readiness of his local church and understands that this will take time and teaching. Nonetheless, he understands the need to build a bridge for the next generation of preachers and plowboys! He is demonstrating benevolence as an outgrowth of Christ-honoring compassion for the pastors, church planters, missionaries, and plowboys of the next generation.

My plea

So, here I’ve made my plea, a plea that has been stoked and burning in my heart for months now. Please, know that this is a plea, not an attack. This is my plea for consistency, the Great Commission, commitment, and for compassion! For some reading this, you settled this issue a long time ago and may wonder, What’s taken him so long; where has he been!?! I’m grateful that you’ve already worked through this. To be honest, I’ve not written this first and foremost for you. I am addressing my plea to the next generation of servants, as well as those who are leading, training, and equipping them, hoping that the limitations of the KJVO position will be acknowledged. And that a recognition of the need for updates to the KJV—even from among modern TR-based translations already available—will be accepted. I’m pleading, for the sake of the plowboys of our day: let them have access to a Bible in their modern English, so that they can have words easy to be understood, so that they can know Christ, so that they can grow, so that they can be all the more effective as representatives of Jesus Christ in their generation, so that our God may be glorified! I’m grateful that in echoing William Tyndale’s plea for the plowboy, it will not end in my being burned at a literal stake—although I may face a metaphorical one of sorts! That’s a risk I’m willing to take. If Tyndale can pay the price that he did, then whatever small price I may pay is worth it. I echo the perspective of Dr. Surrett and cling to it: Bible translations should not be a test of fellowship. I’m grateful for all of my friends who are KJVO, and I intend to do everything I can to maintain those friendships, even as my conscience affirms my position on this issue with the truth of God.

October 6th is the 488th anniversary of the martyrdom of William Tyndale. The testimony of eyewitnesses at his execution tells us that Tyndale’s last words were actually a prayer: “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.” With that the executioner strangled him and lit the pile. Two years later, God would answer his prayer when Henry VIII authorized the limited distribution of the Matthew’s Bible, which was largely Tyndale’s work. The plowboy finally had the Bible in his vernacular. My prayer, as I close this plea, is simply, “Lord, open our eyes, so that the plowboy of our day can have the Bible he so desperately needs in his own English!”

William Tyndale is arguably the most important figure in the history of the English Bible. According to David Daniell, the renowned historian, over 80% of our NT derives from Tyndale’s translation work.14David Daniell, The Bible in English: Its History and Influence (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003), 136. And of the OT books he translated, he has been followed an estimated 76% of the time by subsequent translations.15Brian Moynahan, God’s Bestseller: William Tyndale, Thomas More, and the Writing of the English Bible—A Story of Martyrdom and Betrayal (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2003), 1.

All of this came from a man who lived most of his adult life on the run, exiled from his native country—and who was ultimately betrayed and burned at the stake as a martyr for his consuming desire to make the Bible accessible in the English language of his day. For me, however, one of the most poignant scenes of Tyndale’s life took place when he challenged the blasphemous statement of a learned Roman Catholic, who had just boasted, “We were better without God’s laws than the Pope’s.”16R. Demaus, William Tyndale: A Biography (London: The Gresham Press, 1871), 63.

Tyndale’s passionate reply echoes in my soul 500 years later:

If God spare my life ere many years, I will cause a boy that driveth the plough, shall know more of the scriptures than thou dost.17David Daniell, William Tyndale: A Biography (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2001), 79.

His heart yearned to translate the Bible into such a simple vernacular that the plowboy of England could read and understand the very words of the living God. My plea is that Tyndale’s passion would ignite my generation to such a degree that the plowboy of today can have God’s Word in the English of his day.

William Tyndale, father of the English Bible

My plea for consistency

My plea, first of all, is for consistency. For my entire Christian life I have hailed from fundamental Baptist Christianity. I have used only the King James Version in all my preaching and teaching, and I continue to have profound love and appreciation for the KJV. It has a prominent place not merely in Bible history but in my personal history. This being said, over the last 18 months I have come to the hard-fought and honest conclusion that the thoughtful acceptance and use of faithful modern versions is not at all inconsistent with our principles, nor our past as fundamental Baptists.

In reality, our principles actually argue the case for the acceptance of good current translations, including those translations which hold firmly to a TR-based tradition. We rightfully disdain the mindset of the Dark Ages that restricted access to the Bible from the common man, not only by keeping it chained up in churches, but also metaphorically by keeping it chained up in language that he couldn’t understand! The entrance of God’s Word gives light; it gives understanding to the simple. Common people heard Jesus gladly. Paul in 1 Corinthians 14:9–11 argued for words “easy to be understood” so that meaning and ultimately life-changing edification could be experienced. Interestingly, the KJV translators used this very passage in their preface to the 1611 as a justification for their translation work. Their arguments in that preface also justify the ongoing need for future translations and updates beyond their own work. One of the marvels of the day of Pentecost is that every man heard the wonderful works of God in his own language. We must realize that because of natural changes which occur over time in a language— words “die” and words change meaning within a language—that Jacobean and Elizabethan English are not the English of the 21st century. So even the gracious action of God recorded in Acts 2 is a precedent for our understanding the need of and accepting updates to our Bibles through current translations, so that men can hear and understand, in their own language, the wonderful works of God.

For years I have heard, from within our own circles, the openness for updates to the KJV, but with the passing of time I’ve come to see that this openness is more theoretical than actual. Many viable options that have been offered since the mid-’70s, when I was born, get shot down with various attacks or excuses. I’m increasingly convinced that these excuses are not as much based on principle but more on the politics of our fundamental Baptist circles. Sadly, we have let extremists define the terms of the debate over English Bible translation, and in so doing we are constantly painting ourselves into smaller and smaller extra-biblical corners. We’re defending traditions about the Bible that God neither revealed nor commanded in His Word, and all the while adamantly seeking to avoid association with Ruckmanism. Ironically though, the leaven of Peter Ruckman’s aberrant teachings has infiltrated our doctrine of bibliology more often than is admitted or recognized. For years, my Dad, a Baptist pastor of more than 50 years, has colloquially observed that these discussions often devolve into men trying to be “righter than right.” Truth be told, becoming more right than right can lead to error; just ask the Pharisees!

Furthermore, consistency demands that we recognize another aspect of this issue. So many of the accusations that are leveled against good, viable, modern, even TR-based updates to the KJV, could just as well have been used against the KJV when it was first released. One of the go-to criticisms against modern versions is the presence of alternate translations in the margin or footnotes, and, yet, so it was with the original KJV 1611. The publication of modern versions is often criticized for being economically motivated, and yet a study of the history of the KJV exposes the fact that making money was unquestionably a significant part of what drove its publication.18“Since the time of Henry VIII, Bibles printed within England by official sanction—such as Matthew’s Bible, The Great Bible, and the Bishop’s Bible—were subject to a trade monopoly. The monarch granted a ‘privilege’ to favored subjects allowing them a monopoly on the production of certain types of Bible—an honor or favor usually indicated with the word cum privilegio on the title page of the Bible in question. The crown, in turn received a proportion of the ‘royalty’ paid to the holder of the privilege. … It will thus be clear that the use of the King’s printer for this important new translation did not rest upon any perception that this would ensure a more accurate or reliable printing, but upon the belief that this was potentially a profitable project that would bring financial advantage to Barker and his partners.” Alister McGrath, In the Beginning: The Story of the King James Bible and How It Changed a Nation, a Language, and a Culture (New York: Anchor Books, 2001), 198–199.

All of the translators were paedobaptists. All things considered, while we’re grateful for the remarkable place the KJV holds in the history of the English Bible, we should collectively shudder when we hear of a fundamental Baptist pastor from a major conference platform contending that in the same way the Spirit of God came on the virgin Mary at the conception of Jesus in her womb, so He hovered over Hampton Court as the translators did their work from 1604–1611. I know of no other way to describe this but as heresy, regardless of how many “amens” it garnered. And the KJV translators definitely would not have said an amen to this claim! In their preface they specifically refute the claim that they were inspired like the apostles.20“[There is] no cause therefore why the word translated should be denied to be the word, or forbidden to be current [that is, circulated], notwithstanding that some imperfections and blemishes may be noted in the setting forth of it. For [we ask:] whatever was perfect under the sun, where Apostles or apostolic men, that is, men endued with an extraordinary measure of God’s Spirit, and privileged with the privilege of infallibility, had not their hand?”

My point in bringing these issues up is not to attack the KJV, but rather to further my plea for honesty and consistency. Can I simply say it this way? The KJV was a modern version in the first half of the 17th century. When the KJV entered the Bible market of its day, the very same reasons that have been used to dismiss its modern counterparts since the 1970s were true of the KJV as well. The KJV was not immediately accepted, and it actually took decades to become the primary Bible of the English-speaking world. In fact, when Miles Smith penned the preface to the KJV, he quoted from the Geneva Bible. After the publication of the KJV, a number of the translators not only continued to use the Geneva Bible in their writing and preaching, but several were also actually a part of later efforts to update the KJV for subsequent printings and editions.21Gordon Campbell, Bible: The Story of the King James Version (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), 116–117.

So, consistency with our principles necessitates that we be willing to accept updates to the KJV—such as are already available—and that we admit that the very arguments that are often used to “disqualify” these modern, TR-based updates (such as the NKJV, MEV, KJV21, KJVER and SKJV) could have been leveled against the KJV itself.

The frontispiece to the 1611 KJV.

If Spurgeon was calling for updates in his day, then what does that mean for us today? We must acknowledge, as our fundamentalist predecessors did, that the KJV is subject to the limits of translation, as well as to those normal changes that occur in a language over time, and therefore, of necessity, would need to be updated. This was the prevailing view of fundamentalism up through the 1970s, before the errors of the novel KJVOnlyism of David Otis Fuller, Peter Ruckman, Jack Hyles, and their protégés rose up from our midst. Therefore, it is consistent with our past as fundamental Baptists to recognize the need not only for updates to the KJV, but also to allow room for them.

My plea for the Great Commission

My plea for the plowboy is based, secondly, on the commission, The Great Commission. It is in the spirit of Tyndale that I am compelled to make a plea for the plowboys of our own day to any of my brethren who will read this. The plowboys of our world need a Bible they can understand just as much as the plowboys of Tyndale’s world did. It is estimated that the literacy rates in the 16th and 17th centuries were 16% and 30% respectively. While the overall rates of literacy in our world today may be higher, it is still staggering to consider that an estimated 54% of adults in the US read at a 6th grade reading level or below. Twenty-one percent of adults 18 and above in the US are considered functionally illiterate—a full fifth! And, what we can’t miss is that these statistics are based on reading modern English, not Elizabethan English—and there is a profound difference between them. The plowboys are still in desperate need of God’s Word in their language, and the answer is not to teach them Elizabethan English.

More and more, we’re hearing of the struggles of young missionaries and church planters laboring to use the KJV in countries that may speak an elementary level of modern English, but in a bilingual or even trilingual context. These countries, however, would barely qualify as an ESL setting, if even an ETL or EFL level.23English as a third or fourth language. Yet because Wikipedia tells us that places like the Solomon Islands or Liberia or The Gambia speak English, some American fundamental Baptists insist that the missionary use the KJV. The plowboys of numerous mission fields struggle enough as it is with modern English without being pressed to use a Bible written in Elizabethan English—an English, by the way, with which a growing number of Americans struggle. In truth, pastors, and churches in the multi-ethnic inner-cities of the US are facing the same dilemma as their brethren on foreign fields. Admittedly, there are implications of this reality which are a tough pill for some to swallow, but a solution is at hand. The plowboys of our inner-cities need access to a Bible they, too, can understand.

We need to acknowledge that there’s a sense in which those of us who’ve only known and used the KJV are not the best judges of how desperate the plowboy’s situation really is. For me, processing the Elizabethan English of the KJV is pretty much second nature after over four decades of near daily interaction with it. But fewer and fewer people in the English speaking world have this as their background. Recently, for the sake of comparison and study, I have been doing daily reading in some modern English versions, in conjunction with my reading in the KJV. When I was sharing this with a good friend from a similar background to mine, he asked me if the modern versions were really all that much easier to understand. As I analyzed his question, it hit me that I’m not a fair judge to do such a comparison. When I read the KJV, my mind has a pre-programmed, “update-a-word” mechanism that automatically tells me that “prevent” actually means “to go before,” and that “let” means “to restrain,” and “conversation” means “citizenship” in Philippians 3:20 and “manner of life” in 1 Timothy 4:12, and “untoward” means “perverse,” and “leasing” means “lying,” and “iniquity” means “lawlessness,” and “besom” means “broom,” and on and on I could go. There are hundreds of KJV archaisms, verb forms, syntactical constructions, and words with fundamentally changed meanings that are second nature for me to process. Because of that, I am not a fair judge to do a truly objective comparison between the readability level of the KJV and other modern English versions. The plowboy is the real test. Can the plowboy understand KJV English? That is the question. And so it is for the plowboy that I make my plea. He needs a Bible, both reliable and readable, that he can understand. Reliability and readability are not mutually exclusive, rather they are interconnected. One does not have to be sacrificed for the sake of the other. God’s Word gives us the expectation for both. In fact, accuracy in translation is a two-sided coin. To focus on accuracy from the original language without due consideration of the accuracy of understanding—or readability—in the receptor language is to miss half of the work of good translation. Not only was this William Tyndale’s heartbeat, but I can also say that it is God’s heartbeat! In fact, it is God’s will!

Admittedly, a missionary on the field or a church planter in the inner city can use the KJV to preach, teach, and disciple in the public setting by implementing his pre-programmed, update-a-word mechanism, and he can do a decent job at it (though it will cost him valuable preaching time defining archaisms for his hearers). However, most of the people to whom he’s preaching likely do not have one of those mechanisms in their brains. What are they to do when they go home and try to read the Bible themselves? Do they become dependent on their pastor to explain what the Bible means? It pains me to say it, but it sounds very Catholic, not Baptist, when the pastor becomes indispensable to a person’s knowledge of what the Bible says. Part of what set me on these last 18 months of study and growth is the struggle of my younger brother, Michael, a missionary church planter in the Solomon Islands. I’ll never forget those long, uncomfortable phone calls that first came early in 2023, when he informed me that he was going to begin using the NKJV. At first, I doggedly resisted and tried to talk him out of it, mostly out of my fear of the political fallout. However, as he began to share the reality of his situation with me, as well as the reading he’d been doing, I became slowly, but clearly convinced to make the plea you now have in front of you. Part of his burden was not just the need for a modern English version to be preached in the public setting of the ministry there, but more than anything, his greater burden was for the discipleship and growth of the individual believers and families in their homes. I can still hear his heart, “Nathan, my people need a Bible they can understand at home as they daily seek to know God and lead their families, and they are not getting that from the KJV with its archaic English.” Based on principles like those I related earlier, and for the sake of the people God has called him to evangelize and disciple in the Solomon Islands, he made the decision to use the NKJV. Less than a week after he formally asked his mission board for permission to use a TR-based modern English translation so that his people could understand God’s Word both in public ministry and personal reading, he was removed from that board. He paid a dear price for his convictions, losing approximately half of his support and some friendships, too. But God has vindicated him. Everything he lost has been regained and much more. The work there has grown not only numerically but also, more importantly, in a spiritual way—because the plowboys of the Solomon Islands have a Bible they can better understand. And may I say that Michael is not alone in his dilemma and decision. His situation is increasingly common. So, my plea is based on the Great Commission. And, without any needless offense, I want to goad our consciences with this thought: A tradition such as KJVOnlyism seriously needs to be re-evaluated, if not relinquished, when it becomes an impediment to the Gospel of Christ and the growth of believers, whatever their geographical location.

My plea for commitment

Thirdly, from my heart for the plowboy, I want to plead for a commitment in two particular areas: a commitment to read and a commitment to reason.

A commitment to read

Over the last 18 months, I have purchased 30+ books on this issue, in addition to those I already owned. Some of those books have been agreeable to the position I was taught, but others have not. While some have not been agreeable, they still have an unquestioned fidelity to the Scriptures, a genuine Christlike kindness to their spirit, and a lucidity to their reasoning. All of them have been written by authors who have a high regard for the KJV, even if they advocate for the use of contemporary English translations. They all, with the exception of a couple of historians, would profess to be born-again believers who, as best I can determine, fit firmly in the evangelical or fundamentalist circles and who have a deep love for God’s Word. Reading more widely on this subject has edified me, opened my eyes, exposed me to significant blindspots that had limited my own thinking, convicted me that certain of my own views needed to be amended—and, all along the way, deepened my love for the Scriptures to a greater level than ever before. None of this reading has undermined my confidence in the Word of God; it has only strengthened it! This being said—and I hate to admit this—but in our circles, we are often guilty of doing our reading in an echo chamber on the KJV issue. I plead with you to read scholarly, balanced histories of the KJV like those I’ve referenced in the footnotes. Read the Translators to the Reader preface of the KJV along with detailed explanations of its intent; this is key to understanding how the translators themselves viewed their work. Read what authors on the “other side” of the version debate write regarding both their position and their critiques of KJVOnlyism. Read books on the history of the English language. Read books on translation philosophy and the agonizing, imperfect, and developing work that it always is. Above all, read the Bible for understanding, consciously depending on the Spirit of God as the Divine Teacher, to give you the clearest knowledge of Christ possible. I have had to discipline myself to make sure that even as I’ve done a gargantuan amount of reading about the Bible, that I stay in the Bible. And, in the interests of full transparency, I will admit that as I’ve read from some of these modern versions, I’ve had numerous “light-bulb” moments, as passages that I’d struggled understanding to this point in the KJV, came to clarity through the wording of a modern English version. In those moments, I was a plowboy. All of this reading has stirred this growing plea within me for the plowboys of my generation, and the next, and the next!

A commitment to reason

I’m also pleading for a commitment to reason, that is, to right thinking about the KJV issue. I’ve been embarrassed in some instances and convicted in others, as it relates to how KJVO advocates will attempt to support their position with faulty reasoning and logical fallacies. For instance, there are many wonderful passages in the Bible which speak to the supernatural nature and characteristics of Scripture in every generation, but to appeal to those passages as authority for making an exclusive claim of translational absolutism for the KJVO position is untenable. Whatever your view on the antecedent of the pronoun “them” in Psalm 12:6–7, David was not referring to the KJV alone when he penned these verses 3,000 years ago. Nor was he referring to the KJV alone when he wrote Psalm 138:2, as I heard a preacher contend at a large national conference just last year. This is the same preacher who also propagated the heretical concept that just as the Spirit of God came upon the virgin Mary to conceive Jesus in her womb, so the Spirit of God came upon the translators of the KJV as they did their work from 1604–1611. To say it bluntly, the KJV translators would have rejected such an outrageous comparison. The “incorruptible seed” of 1 Peter 1:23, is not referring to the KJV, as Jack Hyles taught in the 80s. Praise the Lord that folks are being born again by means of modern Bible versions. Modern versions are not the “corruptible seed,” nor are they an enemy of soul-winning. These passages and others are regularly used by KJVO advocates to support translational absolutism, and that is wrong thinking. One has to ask what did these passages mean before the Hampton Court Conference? To which texts, copies, or translations did they refer before 1611? What do they mean for believers in the rest of the world where there has never been a KJV? Without oversimplifying the answer to this question, these passages refer to the Word of God settled forever in Heaven, given to mankind in the originals, and passed on by faithful copies and translations to every generation in every location and language!

Furthermore, it is illogical to hold the KJVO position when the translators themselves were not KJVO by any definition. And too often KJVO advocates resort to ad hominem attacks on men who do not agree with them. This is frequently what happens when a person recognizes that he’s lost the logical high ground of truth or does not fully grasp the issues at hand. Worst of all, it is not Christlike! Dr. Charles Surrett, my former professor and colleague, regularly reminded us, “Our disposition is as important as our position.” How you say what you say is as important as what you say (Colossians 4:6). A viable position can be discredited by a bad disposition! It is also inconsistent and faulty reasoning to make the KJV the standard by which other translations are judged. Fidelity to the originals, not likeness to another translation, is the standard by which a good translation is to be judged. KJVO advocates will look at a particular passage in the KJV and then accuse another version of undermining cardinal doctrines of Scripture because a word is “omitted” in the parallel passage of that version, and yet, in so doing they fail to acknowledge two vital factors: 1) That the doctrine in question is still clearly taught in numerous other passages in that version, but, even more importantly to realize, 2) If comparison between versions is the standard, there are passages where a modern version includes a “key” word, and it is actually “omitted” in the KJV.24Matt 16:21; Matt 27:50; Mark 16:19; Acts 10:48; Acts 24:24; Rom 8:11; Rom 9:5; 1 Cor 6:11; 2 Thess 2:8; 2 Peter 1:1; Rev 1:8; Rev 4:11.

Does this mean that the KJV is guilty of undermining key doctrines of Scripture? Could this not be a case of the “pot calling the kettle black,” or the need to realize that this road runs both ways? It must be kept in mind that the KJV itself is the fruit of translation work, not the foundation by which other translations are to be judged!

Another caveat: we should be wary of the simplistic distinction that is often made regarding formal and dynamic equivalence translations. There are actually more than two legitimate forms of translation. And often, multiple forms are necessary in a single work in order to translate accurately and accessibly! However, KJVO proponents often speak of the absolute superiority of the KJV based on its exclusivity as a formal equivalent translation—but then fail to note that there are occurrences of dynamic and functional equivalence even in the KJV.25Kenneth L. Bradstreet, The King James Version in History (Enumclaw, WA: Pleasant Word, 2004), 120–122. For example: the KJV translators used “God forbid” in numerous passages and “God save the King” in 1 Sam 10:24; 2 Sam 16:16; 2 Kgs 11:12; and 2 Chr 23:11. Both are accurate translations; neither is a literal one.

So, I plead with my brethren, be committed to reading and reason—right thinking! Avoid non sequiturs, logical fallacies, and inconsistencies.

My plea for compassion

Finally, in my plea for the plowboy, I ask for there to be compassion! Assuming that most who read this are Baptist, or at least Baptistic, I plead for compassion based on our distinctives. I’ve periodically noted, on issues like this, that some brethren actually become “half-Baptists.” They seemingly ignore distinctives like the autonomy of the local church, the priesthood of the believer, individual soul liberty, and even the Bible as our sole rule of faith and practice. That’s four out of eight missed, thus producing a “half-Baptist.” I reference my friend Dr. Charles Surrett again. He has graciously maintained a steady TR/KJV position for years, and has written extensively on his reasons for doing so. Men who do not agree with him have testified to the responsible and careful manner in which he has articulated and held his position. In his book, Which Greek Text? The Debate Among Fundamentalists, he made this simple, but profound statement, “In summary, since God did not promise to inspire future translations, there is no Biblical basis to believe in their inspiration, and the issue of translations should not become a test of fellowship.”26Charles L. Surrett, Which Greek Text? The Debate Among Fundamentalists (Kings Mountain, NC: Surrett Family Publications, 1999), 104. May it ever be so!

Compassion can also be expressed as we strive to maintain balance. Balance is not a static position; it requires constant adjustment. And adjustment is definitely needed on this issue for the sake of the plowboy, as well as those of the coming generations who will minister to them. We do the next generation no favors if we double down on this issue, painting ourselves (and unfortunately them) into an even tighter corner. All the while, the natural changes occurring in the English language with the passage of time make KJVOnlyism all the more untenable and the Elizabethan English of the KJV progressively more unintelligible. May we strive for balance—moderation, reasonableness (Philippians 4:5)—on this issue.

It follows also then that there should be a benevolence that marks us, as we seek to demonstrate Biblical compassion: benevolence both for the needs of the plowboy and for the next generation of pastors, church-planters, and missionaries who will win and disciple them. This benevolence can be demonstrated by giving them legitimate room to implement the choices they need to make in order to use the best Bible possible to reach the plowboy of their generation in their corner of the harvest field. This spirit of Christlike benevolence will also keep us from automatically accusing a young man of compromise who, for the sake of the plowboys where he labors, is compelled to use an updated version. This slippery slope argument is yet another fallacy of logic that is often motivated by fear, not faith or fact!

Last year I was deeply challenged and encouraged as well by my conversation with an older pastor friend, who is a faithful fundamental Baptist. He anticipates ten more good years of pastoring before retirement and is contemplating leading his church to make the change to a good updated version of the Bible in his final years. Part of his reasoning is that he’s the one who has the pastoral capital to do it. This will save his potential successor—almost certainly a younger man—from having to lead in this step forward. This is a benevolence that stems from a compassion for the next generation, reminding me of Will Allen Dromgoole’s classic poem, The Bridge Builder. Granted, this pastor is sensitive to the readiness of his local church and understands that this will take time and teaching. Nonetheless, he understands the need to build a bridge for the next generation of preachers and plowboys! He is demonstrating benevolence as an outgrowth of Christ-honoring compassion for the pastors, church planters, missionaries, and plowboys of the next generation.

My plea

So, here I’ve made my plea, a plea that has been stoked and burning in my heart for months now. Please, know that this is a plea, not an attack. This is my plea for consistency, the Great Commission, commitment, and for compassion! For some reading this, you settled this issue a long time ago and may wonder, What’s taken him so long; where has he been!?! I’m grateful that you’ve already worked through this. To be honest, I’ve not written this first and foremost for you. I am addressing my plea to the next generation of servants, as well as those who are leading, training, and equipping them, hoping that the limitations of the KJVO position will be acknowledged. And that a recognition of the need for updates to the KJV—even from among modern TR-based translations already available—will be accepted. I’m pleading, for the sake of the plowboys of our day: let them have access to a Bible in their modern English, so that they can have words easy to be understood, so that they can know Christ, so that they can grow, so that they can be all the more effective as representatives of Jesus Christ in their generation, so that our God may be glorified! I’m grateful that in echoing William Tyndale’s plea for the plowboy, it will not end in my being burned at a literal stake—although I may face a metaphorical one of sorts! That’s a risk I’m willing to take. If Tyndale can pay the price that he did, then whatever small price I may pay is worth it. I echo the perspective of Dr. Surrett and cling to it: Bible translations should not be a test of fellowship. I’m grateful for all of my friends who are KJVO, and I intend to do everything I can to maintain those friendships, even as my conscience affirms my position on this issue with the truth of God.

October 6th is the 488th anniversary of the martyrdom of William Tyndale. The testimony of eyewitnesses at his execution tells us that Tyndale’s last words were actually a prayer: “Lord, open the King of England’s eyes.” With that the executioner strangled him and lit the pile. Two years later, God would answer his prayer when Henry VIII authorized the limited distribution of the Matthew’s Bible, which was largely Tyndale’s work. The plowboy finally had the Bible in his vernacular. My prayer, as I close this plea, is simply, “Lord, open our eyes, so that the plowboy of our day can have the Bible he so desperately needs in his own English!”